-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Grants

-

IDF surveys

-

Participating in clinical trials

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Clinician education

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Grants

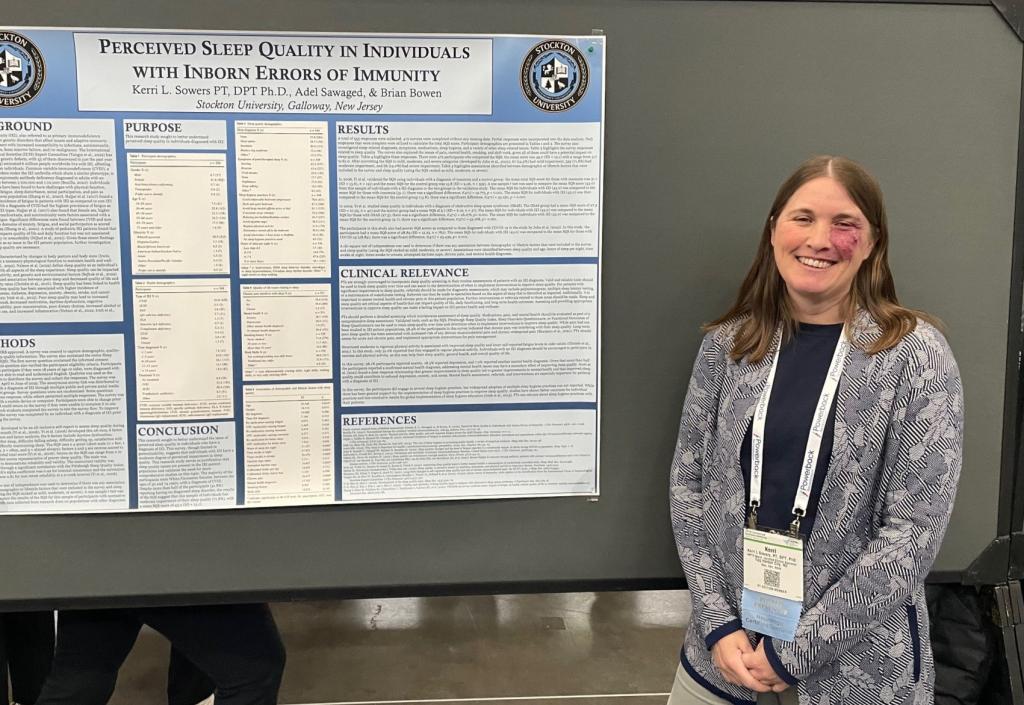

On most days, Dr. Kerri Sowers starts her day caring for and riding her two horses before heading to work. As a physical therapist (PT) turned health professor, Sowers is an expert on the impact of exercise on the body.

“I believe in physical activity for everyone. I know that if I am not physically active on some level, it's not good for me,” said Sowers, 43. “For me, being out with the horses, riding, gardening, things like that, I feel so much better mentally and physically.”

Sowers is diagnosed with common variable immune deficiency (CVID). Although managing her health can be complicated, that hasn’t stopped her from achieving both her professional and personal goals.

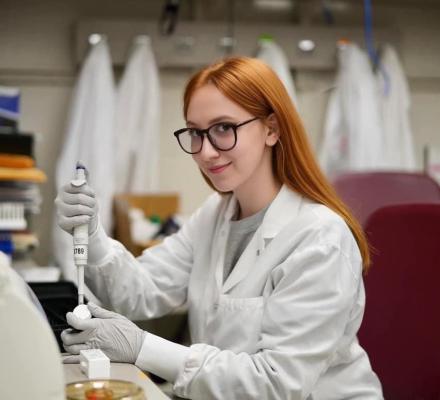

After earning her Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) degree and working for six years in the field, Sowers earned a Ph.D. in PT and became a health science professor at Stockton University. For her dissertation, she researched exercise behaviors and perceptions in the PI community by surveying individuals about their participation in exercise routines.

“A lot of people were just afraid that if they exercised, it would make them sick and make them feel worse. And for other people, fatigue was the overwhelming issue. They were too tired to exercise,” explained Sowers.

In another study she conducted on the effects of moderate-intensity exercise on individuals with PI, Sowers found that people remained healthy when adopting an exercise program.

“The consensus is that as long as you're not doing high-intensity, Olympic-level, Ironman-level workouts, you're probably not going to impair your immune system enough for it to have an impact. The thought is a low to moderate level is protective on some level,” said Sowers, who suggests activities like walking, dancing, and tennis. “People just need to move more.”

Growing up, Sowers stayed fit through competitive horseback riding and started her own horse training business after college. She switched to the PT field for greater financial stability and worked in hospital trauma units, specializing in treatment for patients with neurological challenges like strokes and spinal cord injuries.

Though a hospital may seem like a risky environment for a person with PI, Sowers said the required mask, gloves, and gown provided better protection from infection than she would otherwise have in a typical PT clinical setting.

“My immunologist was freaked out and I said at least in the hospital I can take precautions,” said Sowers.

Sowers enjoyed PT but sought a profession with more room for growth. When a position as a health science professor opened at Stockton University, where her mother worked as a chemistry professor, it was a natural fit for Sowers.

Teaching allows her to conduct research and provides her with the flexibility to pursue another passion—serving as a national and international classifier for para-athletes competing in equestrian events.

As a classifier, Sowers performs physical therapy assessments on para-athletes to determine their level of impairment for competition. Athletes are grouped by abilities to make the competition more equitable.

“We have a system that we work with that helps us evaluate the athletes’ different disabilities and impairments so that we kind of level the playing field as best we can,” explained Sowers.

A perfectionist who never backs down from a challenge, Sowers admits that she can be a workaholic and that her drive to prove she can accomplish difficult tasks sometimes affects her health.

“There are times when I will push myself past the point of exhaustion, and then I will pay for it. I'm still not good at listening to my body that way. That's been a hard lesson for me,” said Sowers.

Missing the red flags

Sowers received her CVID diagnosis at 31, but before that, doctors failed to follow up on opportunities to uncover her primary immunodeficiency (PI). Frequent respiratory infection, chronic sinusitis, adverse reactions to allergy shots, an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) illness that led to her missing five months of freshman year in high school, a staph infection that required hospitalization, gastrointestinal (GI) problems, and low responses to vaccines all slipped by the attention of primary care providers and specialists.

“I look at all this stuff in hindsight, and I think, how did it get missed? I should have been diagnosed earlier because if you look back into my medical chart and records, there were a lot of red flags that should have been picked up on. But, typical of most people in the PI community, they weren’t,” said Sowers.

Then, during a trip to the emergency room for a GI bleed, Sowers met a gastroenterologist who suspected her issues might be more than irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

“I remember him saying to me, ‘I don't want just to give you the IBS label. I don't know what's going on, but it's not just IBS, and I think you need to start looking for people who have more experience’,” said Sowers. “I still respect him to this day for saying I don't want just to label you and throw you under the rug with everything else.”

Celiac testing showed she had no immunoglobulin A (IgA), and she got fast-tracked into the University of Pennsylvania Health System, where she received her diagnosis.

Finding the right treatment

Sowers experienced drug-induced aseptic meningitis several times when she tried intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement therapy to protect her from infection. The first time she developed a headache but took an over-the-counter pain reliever and felt better. The second time she sought treatment at her doctor’s office for side effects, and it took two weeks to recover. The third time debilitating pain forced her to the emergency room.

“It was like a migraine on steroids. I couldn’t stand up. I had sharp pains in my neck, and it hurt to move. Everything hurt. I was extremely fatigued and just not able to function,” said Sowers, who suffered from headaches and an inability to concentrate and focus for a month.

Sowers said the third bad reaction from IVIG occurred because the pharmacy hadn’t diluted the drug properly, causing the infusion to run at twice the normal rate. She questioned the lower amount of Ig and shorter treatment time when the nurse administered it.

“I thought that it didn’t seem right, but she’d done the checks, and she’d shown me all the labels, and everything looked correct. I didn’t have anything else to go on,” said Sowers. “You have to trust your gut.”

Subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG) replacement therapy didn’t work out much better for Sowers. After a trial administration in the immunologist’s office with the drug representative present, she broke out in hives all over her stomach.

Faced with allergic reactions from both IVIG and SCIG, Sowers consulted one of the top immunologists and PI specialists in the country, Dr. Charlotte Cunningham-Rundles.

“She was just very to the point. She said, ‘You could probably survive without it because you do have some Ig levels and you do have some vaccine protection, but this is not a good quality of life either,’” said Sowers.

Cunningham-Rundles prescribed daily SCIG, unusual back in 2011, said Sowers, and it worked. She tolerated the dose and the infusion rate—one gram infused over two hours—and she continued that regimen for several years. Today, Sowers administers two grams of SCIG four times a week.

With the SCIG, her chronic sinusitis cleared up, and she no longer takes allergy shots. Although it didn’t help her GI issues, she’s thankful for the treatment.

“That was the balance that allowed me a better quality of life,” said Sowers.

Seeking support

Sowers visited her first Immune Deficiency Foundation (IDF) conference in 2012, held in Baltimore, just a few hours’ drive from her home in New Jersey. As a healthcare professional, she sought more information about her diagnosis and treatment so that she could advocate for herself in both medical and work settings.

She didn’t know anyone at the conference but sat down at a table with other women her age and instantly had a strong connection with one person in particular.

“We've become great friends ever since, and we talk regularly. We help each other through medical stuff and have pretty much tried to meet up at all the conferences,” said Sowers.

Choosing the right doctor

Sowers advises others with PI to advocate for themselves when pursuing medical care. The first step in that process is to find the right fit with a healthcare provider. Some are better than others, and all vary in their approach to medicine.

“You know your body, you know yourself. Sometimes you have to find a different match or a different personality that's going to listen to you. Sometimes you might need a more scientific doctor, and sometimes you might need one who's more empathetic. And that's OK. There's no right thing for every person,” said Sowers.

Feel comfortable asking questions and push back if providers ignore your concerns or brush you off, she said.

“Don't let anyone belittle your patient experience because I think that happens a lot, especially with PI and other invisible illnesses where you can get written off. You look great. But doesn't mean your body feels great,” said Sowers.

Sowers said progress is being made to better train healthcare professionals on the importance of listening to patients when they discuss their symptoms and what life is like living with those symptoms but the old mindset of doubting the patient still exists.

“As healthcare providers, we have to remind ourselves that it doesn’t matter what our perception is because we aren’t the patient. It matters what the patient’s perception is and then we need to treat from there,” said Sowers.

Related resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309