-

Understanding primary immunodeficiency (PI)

Understanding PI

The more you understand about primary immunodeficiency (PI), the better you can live with the disease or support others in your life with PI. Learn more about PI, including the various diagnoses and treatment options.

-

Living with PI

-

Addressing mental health

-

Explaining your diagnosis

- General care

- Get support

- For parents and guardians

-

Managing workplace issues

- Navigating insurance

-

Traveling safely

Living with PI

Living with primary immunodeficiency (PI) can be challenging, but you’re not alone—many people with PI lead full and active lives. With the right support and resources, you can, too.

-

Addressing mental health

-

Get involved

Get involved

Be a hero for those with PI. Change lives by promoting primary immunodeficiency (PI) awareness and taking action in your community through advocacy, donating, volunteering, or fundraising.

-

Advancing research and clinical care

-

Grants

-

IDF surveys

-

Participating in clinical trials

-

Diagnosing PI

-

Consulting immunologist

-

Clinician education

Advancing research and clinical care

Whether you’re a clinician, researcher, or an individual with primary immunodeficiency (PI), IDF has resources to help you advance the field. Get details on surveys, grants, and clinical trials.

-

Grants

You don’t have to be an expert to be an effective advocate for vaccines. In fact, anyone can turn the tide against vaccine hesitancy (when people delay or refuse vaccines) simply by talking to their family and friends.

This is the central message of two resources designed to help people from all walks of life understand vaccine hesitancy and make a positive difference in attitudes towards vaccines in their communities.

Online course provides general strategies and COVID-19 information

Addressing vaccine hesitancy has renewed urgency in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health’s “COVID Vaccine Ambassador Training: How to Talk to Parents” is an online course offered through Coursera that takes approximately two hours to complete (and you get a certificate!). It offers great information on the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19, how mRNA vaccines work, and the COVID-19 vaccine development process.

Much of the course information is transferable to other vaccines as well. One of the most useful tidbits is how to approach vaccine conversations so that they are productive. The key: facts alone will not sway most people, so the goal should be building trust. It’s important to listen with empathy, respect, and understanding, and respond to someone’s specific concerns about vaccines rather than just dismissing their point of view.

Three effective strategies for talking about vaccines include:

- Highlighting vaccination as a social norm. Talk about vaccination as though it’s no big deal and a normal part of life. You can also mention how you and others have or plan to get vaccinated.

- Pivoting to the real risks of the disease in question to address myths and misinformation. A lot of misleading information on the COVID-19 vaccines focuses on real vaccine side effects, such as heart inflammation (myocarditis), without the context that such vaccine side effects are very rare, especially when compared to the risk of myocarditis from COVID-19 itself.

- Sharing your vaccination story. Supplementing facts with your own story helps build trust. Sharing the good (“I’m so glad I’m protected now!”) and the bad (“But, man, was my arm sore for the rest of the day.”) shows that you don’t have an agenda.

#vaccinated (almost) #sciencerocks #vaccinessavelives pic.twitter.com/lHORm2W37o

— Katherine (Sorber) Lontok (@ScienceInTheDMV) April 7, 2021

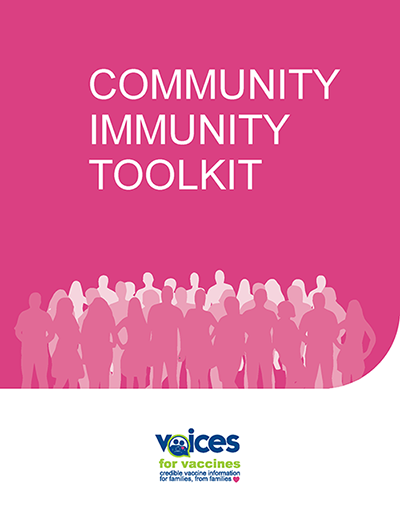

Toolkit makes the case for vaccination as a social responsibility

Routine vaccination is one of the most important public health accomplishments of the 20th century. It is a particular ‘win’ for those who are immunocompromised and may not respond well to vaccines themselves; vaccination provides a barrier to the spread of diseases within a population, known as community or herd immunity, without the risks associated with getting the disease itself. Thus vaccine hesitancy threatens not only individual health but the health of entire communities.

Voices for Vaccines’ Community Immunity Toolkit is a short read, with lots of practical information on getting out into your community to advocate for vaccines. It includes a clear explanation of community immunity and frames vaccination as a social responsibility. However, the toolkit also recognizes that such messaging does not resonate with everyone.

Another way to present community immunity is that the barrier better protects every individual. No vaccine is 100% effective and even those with good vaccine response benefit from the extra protection of community immunity.

Taking cues from both the online course and the toolkit, weaving your personal story as a person with PI into the community immunity framing could be a powerful way to engage those who are vaccine hesitant. The approach makes both a logical and emotional case for vaccines that is hard to ignore.

Related resources

Sign up for updates from IDF

Receive news and helpful resources to your cell phone or inbox. You can change or cancel your subscription at any time.

The Immune Deficiency Foundation improves the diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for every person affected by primary immunodeficiency.

We foster a community that is connected, engaged, and empowered through advocacy, education, and research.

Combined Charity Campaign | CFC# 66309